„Zanussi is one of those authors who have known how to enrich a dialogue with a religious, metaphysical, or scientific content while still keeping it as the most everyday and trivial determination.“ – Deleuze, Cinema 2

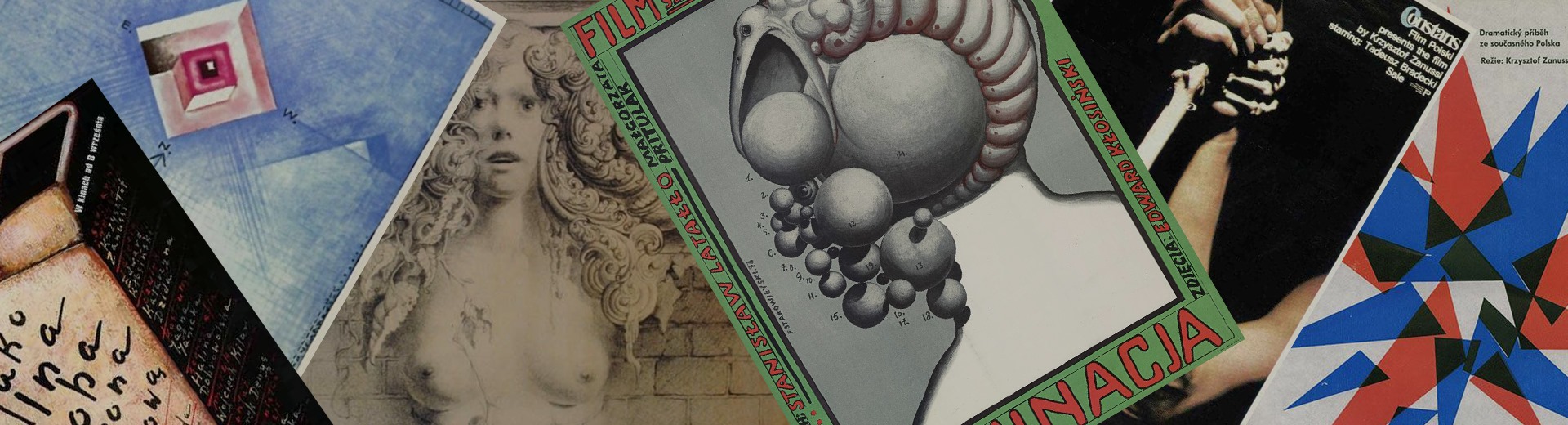

The 23rd edition of Áčko Festival gave us an opportunity to visit Krzysztof Zanussi’s masterclass titled Can dreams become reality?. The polish director accepted the invitation and visited FTF VŠMU. In general, Krzysztof Zanussi’s works do not prioritize or hierarchize human experiences or science over spirit and his characters, Zanussoids, are mostly seeking the truth, meaning of life, true values.

TD: How dreams influenced your creations?

KZ: I don’t want to be too specific, there is a pill, that you can use, when you travel a lot and you want to fight your jet lag. It is an American drug and it makes your dreams far more real. It is melatonin. However, it is only close observations about dreams. Otherwise there are conscious dreams. Those are not the dreams when you fall sleep, you just think about the certain situations, you invent situations, and you do it with your eyes open. These dreams are my scripts.

TD: Critics often mention film directors who have influenced you, such as Bergman or Bresson. What about literary inspirations, texts that enlightened you?

KZ: Balzac, Thomas Mann, Dostoyevsky and Joseph Conrad. Definitely Marcel Proust. Although he is broadly recognized today, probably only a few people are aware that the act of taking the endless number of pictures on your cellphone manifests the same kind of anxiety that Marcel Proust had, as he wanted to capture the time that is running. And he could not. It is not possible. Next, Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampelusa, extremely highly rated, he was the last great European novelist but also Graham Greene with whom I collaborated. I worked in the theatre with many playwrights, and I was particularly interested in Eugène Ionesco.

TD: You were making films during a time of heavy censorship. How did you deal with the constrains of the previous regime?

KZ: That story would be enough for a novel because each film brought us a new story, a new experience. A fight. Many of my films ware slightly wounded by censorship, sometimes it was a painful wound but that was the reality of the time. When censors had no other objections than an artist, I thought I didn’t explore the full field of my freedom. It was a good sign when a censor was angry. But we had to know the limit and play around this border line.

TD: What do you think about contemporary Europe?

KZ: Europe is in a state of a very deep confusion and imbalance. I think it has lost its balance in 1968. The reconstruction of postwar Europe was somehow completed. And ever since 1968 the students’ rebellion started a sort of distraction or deconstruction of Europe. And I think it has now brought us to some kind of a crisis. Even if we have some achievements, that’s undeniable, we must look for a new definition. We must go far beyond this point, we must revise many years and definitely go neither left nor right, neither towards nationalism nor cosmopolitanism, we must find a new identity.