On the documentary Enter Through the Balcony by the Ukrainian director Roman Blazhan

Enter Through the Balcony

Director Roman Blazhan, Ukraine, 2020, 25 min., available on Takflix

I was about four years old when our family house, which was built by my great-grandfather, was confiscated by the state under the socialist rule. Just as my grandparents, my mother and I had to move to a block of flats. We were assigned a small two-room apartment on the ground floor. Without a balcony. My memories of this period could be described by the feeling of fundamental loss, its incomprehensibility and the effort to regain the only reality I knew until then. My early years were spent in the garden, with animals and plants, exploring their microworld. When we moved, for the next six months, I pleaded with my mother to add a small balcony to the kitchen window and place a chicken coop on it. Or rabbits, if they would fit.

Of course, we never added a balcony, but the desire to own one stayed with me. There are two things I really like about apartments: a bathtub and a balcony. Emotionally, they are actually not that far from each other, both elements represent a certain freedom, relief, or an escape. That’s why every time I had spent a long time in New York, I wanted to live in a house with a fire escape (even more so after I watched the film Frances Ha). So far, I only got one chance, but I took it on with grandeur. I made a small perch out of the platform that I was able to climb on from the window of my room. There I was eating, reading, drinking coffee or a beer, thinking, watching the street and eventually started to hang my laundry to dry, which caused a (surprising) uproar not only in the house, but in the whole neighborhood, which culminated in a rebuke from the janitor and his serious statement, uttered with utmost dedication to his position and determination to protect the law: “Fire escape is for escaping fire.” Period.

What, then, is the purpose of a real, official balcony? Everything is, as we gradually learn from the documentary Enter Through the Balcony by the Ukrainian director Roman Blazhan.

A balcony is not just a place – it’s a feeling. That’s the underlying emotion of the documentary that keeps surfacing.

What feeling, specifically? The feeling of the space and of oneself in it. Being able to stay at home and at the same time find yourself in a pleasant extension between the apartment and the public space, which, if we desire, mediates a connection: with the neighbors, with the street, with the weather, the sun, and finally perhaps even with oneself in a certain relaxedness, the possibility to breathe. Light a cigarette, sip a coffee or a drink with the sun shining on your eyelids… The balcony is almost like a small vacation.

The socializing aspect of the balcony culture in the film is relevant in the context of the isolating mass of blockhouses, which radically changed the lifestyle of many residents during socialism. The balcony offers a casual connection with the world around, which is rare especially for the elderly or those who live alone: standing on the balcony and being able to exchange a few words without going out into the street… making eye contact, waving to a neighbor.

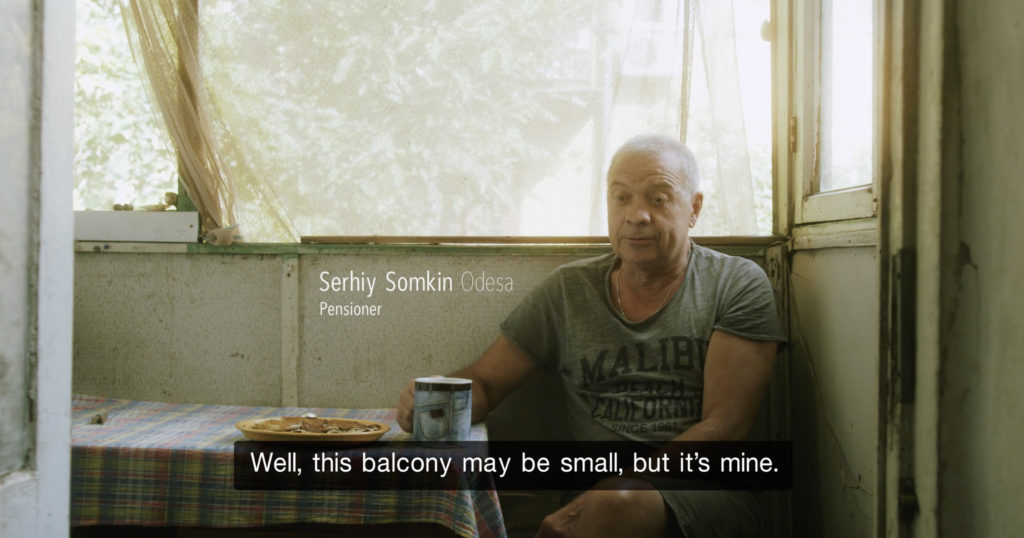

This balcony is small, but mine. This is one of the first and at the same time important sentences of the film, which is articulated (proudly and modestly at the same time) by Sergiy Somkin, a pensioner from Odessa. We start with Sergiy and gradually other places and their stories are revealed to us. With Blazhan, we literally dive into balcony universes and gradually begin to understand the cultural-political context in which the very peculiar and rich Ukrainian balcony culture was born.

Also thanks to the visual qualities of the film, the immersion is soft and pleasant. We travel through different cities (Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv, Odessa, Dnipro…), together with the drone we hover over monstrous apartment buildings, only to immediately land in the magical nooks of balconies, observe their details and listen to stories.

The documentary gradually unfolds not only the stories of different people and the perspective through which they perceive and use this specific space, but also the interesting social and political context of the local balcony culture. It began to expand significantly in the 70s and 80s of the last century.

Kyiv architect Oleksandr Burlaka talks about the illegal or shadow economy of the Soviet Union, a huge part of which consisted of buying, stealing or exchanging materials for self-help construction or improving apartment balconies.

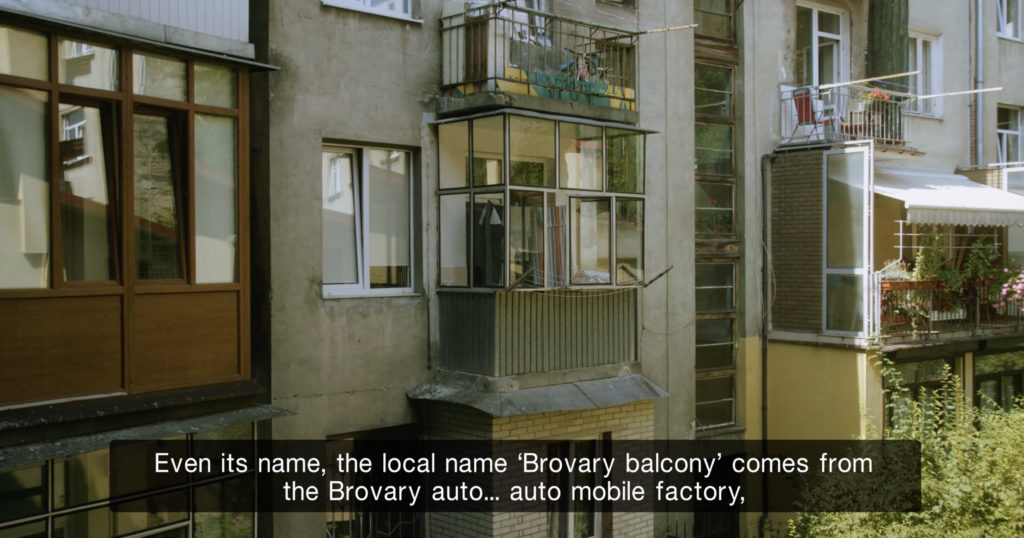

Their aesthetic appearance and the improvements made by inhabitants became an important factor, or even an indicator of socio-economic status. The phenomenon of covering balconies with glass, which also developed in the era of socialism, appears to be particularly significant here. In times of scarcity, especially when it comes to building materials, great improvisation flourished, without taking into account the aesthetic qualities and expression of the building’s architecture as a whole. For many, the balcony represented a precious extra space, which was often turned into an additional storage room and thus solved the lack of storage space in a small block of flats. The term “Brovary balcony” appears repeatedly.

It sounds noble, almost like Biedermeier, but the reality is prosaic… In the city of Brovary, on the outskirts of Kyiv, there was a factory that produced glass for cars. And this glass was perfect for glazing balconies. It was apparently so accessible and practical that its use seems to have developed into a national Brovary “style” prominent for at least a decade. Thus, a status symbol was born – if one didn’t glaze their balcony, it was as if one did not even have it at all, as if one did not know how to live properly.

It is interesting to think about all this in the context of an era that was characterized, at different levels of society, by great uniformity. As the chief architect of the city of Dnipro says in the document, while the blockhouse buildings were identical at the time of their creation, it was the parasitic architecture of the balconies, their glazing or other methods of improving and adding functions that became a space for individual expression and also a mirror of very specific possibilities, means, ideas, and dreams. And a very specific desire to personalize this fragment of space (small, but my own) as best as possible, in my own way, however it can be.

And that’s why today we don’t find two originally identical buildings that look the same. The chilling gray and monotonous mass of the block of flats has been interwoven with its own, self-created microworlds for decades.

Even if it might seem that the balcony culture is also relatively developed in other post-socialist countries, such as Slovakia, after watching Blazhan’s documentary, I got the impression that our Ukrainian neighbors have refined this phenomenon on a much higher level. Either in building improvisational and parasitic structures, which Kyiv anthropologist Tina Polek talks about in the film, or in the (notably touching) soulfulness and love with which they approach the improvement and use of their balconies.

Thanks to the documentary, I realized that the balcony can be approached as a symptom. Similarly, when our bodies manifest their complicated internal processes in different ways, Ukrainian balconies (not solely) and their world are the symptomatic of deeper movements of a social, cultural or economic nature. This aspect is excellently portrayed in the document by incorporating different viewpoints: perspectives of residents, architects, anthropologists, and others are layered here, representing a variety of attitudes and emotions associated with a seemingly simple urban element.

Blazhan’s sensitive and inclusive approach was manifested not only in the selection of respondents, but also formally, in the way they are depicted: each and every one of them on their balcony. This de-hierarchization – of those who understand or decide about architecture and those who use it – encourages the impression that all voices are of equal value. And all together they form the national phenomenon of the balcony as a place and a feeling. The filmmaking approach gave me the impression that Blazhan delivers a consistent statement about the phenomenon and at the same time leaves a lot of room for the power (and charm) of the subjective voices that shape it. After all, this documentary is not just about balconies. It depicts the way in which people united by a specific cultural-geographic space think and act through a prism of a specific local phenomenon.

Architecture serves as a catalyst of expression: Ukrainian balconies represent the materialization of limitations and freedom, values and dreams.

This is the foundation of this narrative: seemingly trivial element such as a balcony enables a discussion about bigger, deeper topics.

But what does it mean to watch Enter Through the Balcony in 2022?

For me personally, it brings up a mixture of different emotions. I am engulfed with sadness and despair knowing that much of what I am looking at probably doesn’t exist anymore or will not soon. Many questions emerged, such as what is now happening to the people whose words I listen to; where are those people now, pictured here in the safety of their homes about which they talk with such love and pride, not knowing what the future holds. That’s what it’s like to watch Enter Through the Balcony today: multi-layered sadness, anxiety, anger – but also a feeling of great gratitude for the fact that it was all (so beautifully and thoughtfully) captured. And that no one can destroy this recording of their existence (neither for them, nor for us).

You may watch Enter Through the Balcony on the TAKFLIX platform.

Roman Blazhan is a filmmaker and producer currently based in Kyiv, Ukraine. He is originally from Donetsk, where he pursued a career in finance. After losing his home due to the outbreak of the Donbass war in 2014, he had decided to change not only a place of residence but also a career path and he started to make films and founded the production company Minimal Movie, which specializes in short films, commercials and documentaries.